INSPIRATION…Maurice Sendak

Posted on 26th October 2013If you ask me, the picture book was one of the very best artistic forms to evolve in the 20th century. It’s up there with the three-and-a-half-minute rhythm and blues song, the animated film, the television drama series, or any other remarkable creative innovation you can think of that came out of the same period.

There were illustrated books for children long before 1900. But something seemed to happen around the time of the first commercial edition of Beatrix Potter’s ‘Peter Rabbit’, in 1902.

A taste developed for short, affordable, colour-illustrated storybooks for younger children. And in the decades that followed, the illustrations in these books became ever less decorative, ever more a part of the storytelling. So, sometimes step by step, sometimes in leaps forward, the special form of the picture book that we know today came to be.

It’s a special form because it’s such a mix of delights. Inside good contemporary picture books you get characters that children love from the opening words…engaging themes…page-turning stories…inventive, skilfully-crafted illustrations…flights of imagination…colour…humour…emotion and – as if all that wasn’t enough – endings which uplift, provoke, surprise (or do all three!)

That’s a lot of delight for an adult reader and child to share – all packed into 12 (or so) double-page spreads.

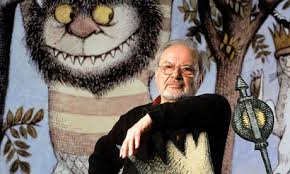

And it would be wrong to speak only of delight. There’s a notable history of picture books going into uncomfortable, shadowy subjects too. And for that aspect of picture-book making, I’d say we should raise our hats to the American author and illustrator, Maurice Sendak.

Sendak was a fiercely independent, honest, funny, questioning character. (Have a watch of this short film, capturing him at home, in his later years. You’ll see what I mean…)

He wasn’t the only one to push back boundaries around what can be in a story for 2 to 6 year-olds. But his picture book, “Where the Wild Things Are” was such a brilliant challenge to the conventions of its day, and became so popular, that it ended up paving a good bit of the way for other challenging picture books that have followed.

The story of Max (the protagonist of ‘Where The Wild Things Are’) is a simple one. It’s a tale of leaving and returning. It’s only 338 words long. But over that short distance, Sendak touches on a many difficult themes: cruelty, uncontrolled anger, punishment, loneliness, ecstatic release and fear (among others.) The ‘wild things’ themselves are wonderfully complex. (Are they going to be friends with Max, or are they going to eat him up?) It makes for one of the most fantastic journeys in all of children’s literature.

And it’s telling that, despite being one of the best known children’s book makers of his generation, Maurice Sendak didn’t like to be described as a children’s author.

He broke the mould with his picture books. He went searching for truths about what it is to be human, whether you’re a child, a grown-up, or somewhere in between. In other words, he approached picture-book making with the sharpness of a genuine artist’s sensibility.

And it has been a wonderful thing for children’s literature that this sensibility found its way into the making of books for very young children.

Picture books could have evolved into pretty, soothing boxes of delight to help parents get children to sleep. Thanks to the likes of Maurice Sendak, they are a much more exciting and wild prospect.